Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it’s investigating the financials of Elon Musk’s pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, ‘The A Word’, which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.

Kim Philby was the quintessential spy, a man who charmed and betrayed in equal measure.

To his colleagues in MI6, he was the consummate professional, rising swiftly through the ranks of Britain’s foreign intelligence service. To Moscow, he was their most prized asset, a double agent who passed secrets for nearly three decades. And to his closest friend, Nicholas Elliott, he was a man capable of the ultimate treachery.

The newly released files from the National Archives offer a vivid glimpse into Philby’s chilling career as a Soviet mole inside MI6, from his recruitment as a young communist in 1934 to his dramatic defection to Moscow in 1963.

Packed with confessions, lies, and betrayals, these documents reveal the calculated deceit of a man who changed the course of Cold War espionage and whose actions led to untold deaths.

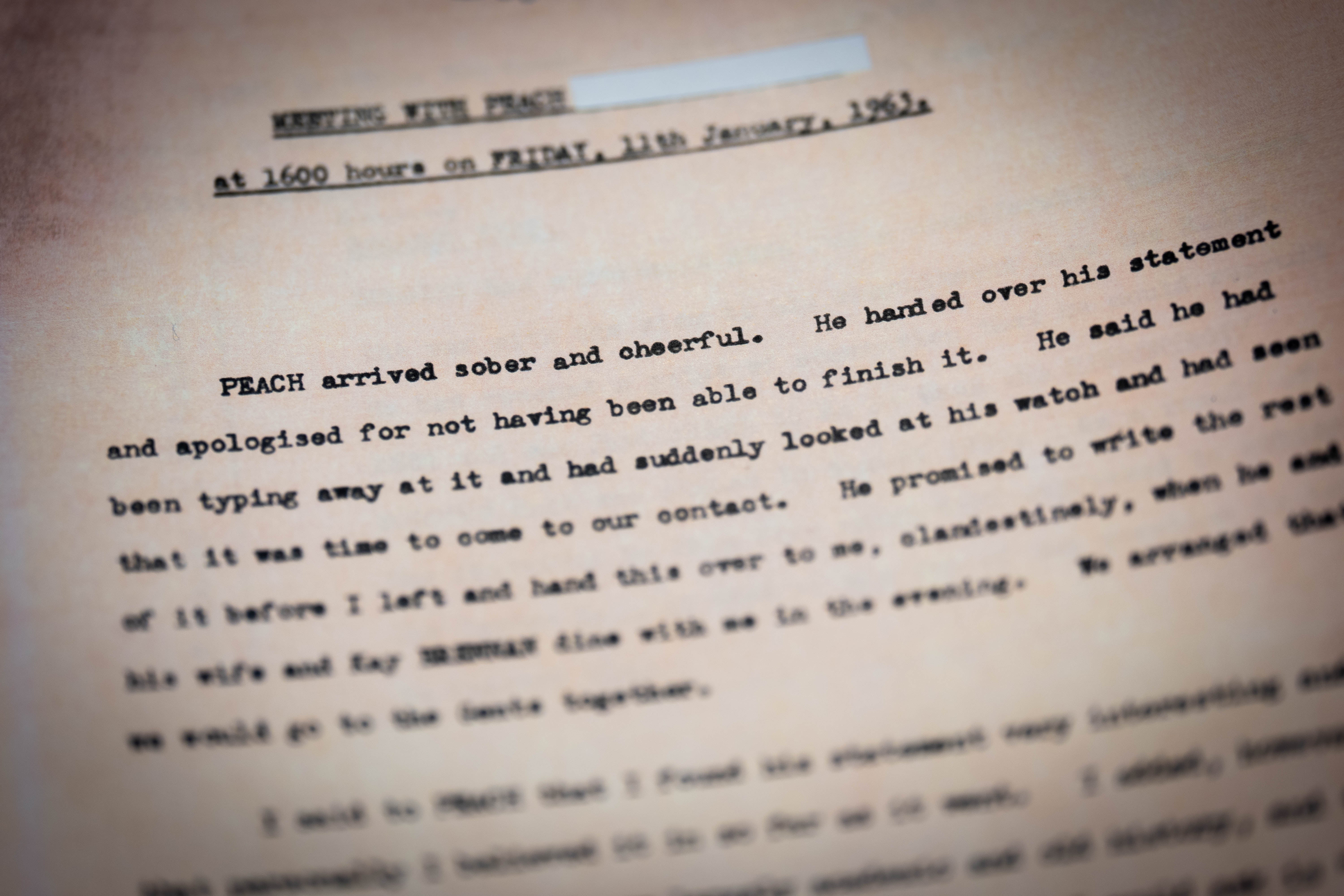

Philby’s confession to Elliott stands out as the most extraordinary document in the newly released files – a carefully crafted mix of truths, evasions, and outright lies. The recorded conversation, secretly captured by Elliott, allowed Philby just enough time to alert his KGB handlers and arrange his escape.

Now made public for the first time, the transcripts offer an unparalleled glimpse into the psyche of Britain’s most infamous traitor and the devastating personal betrayal of a friendship that once seemed unshakable.

The Cambridge Five

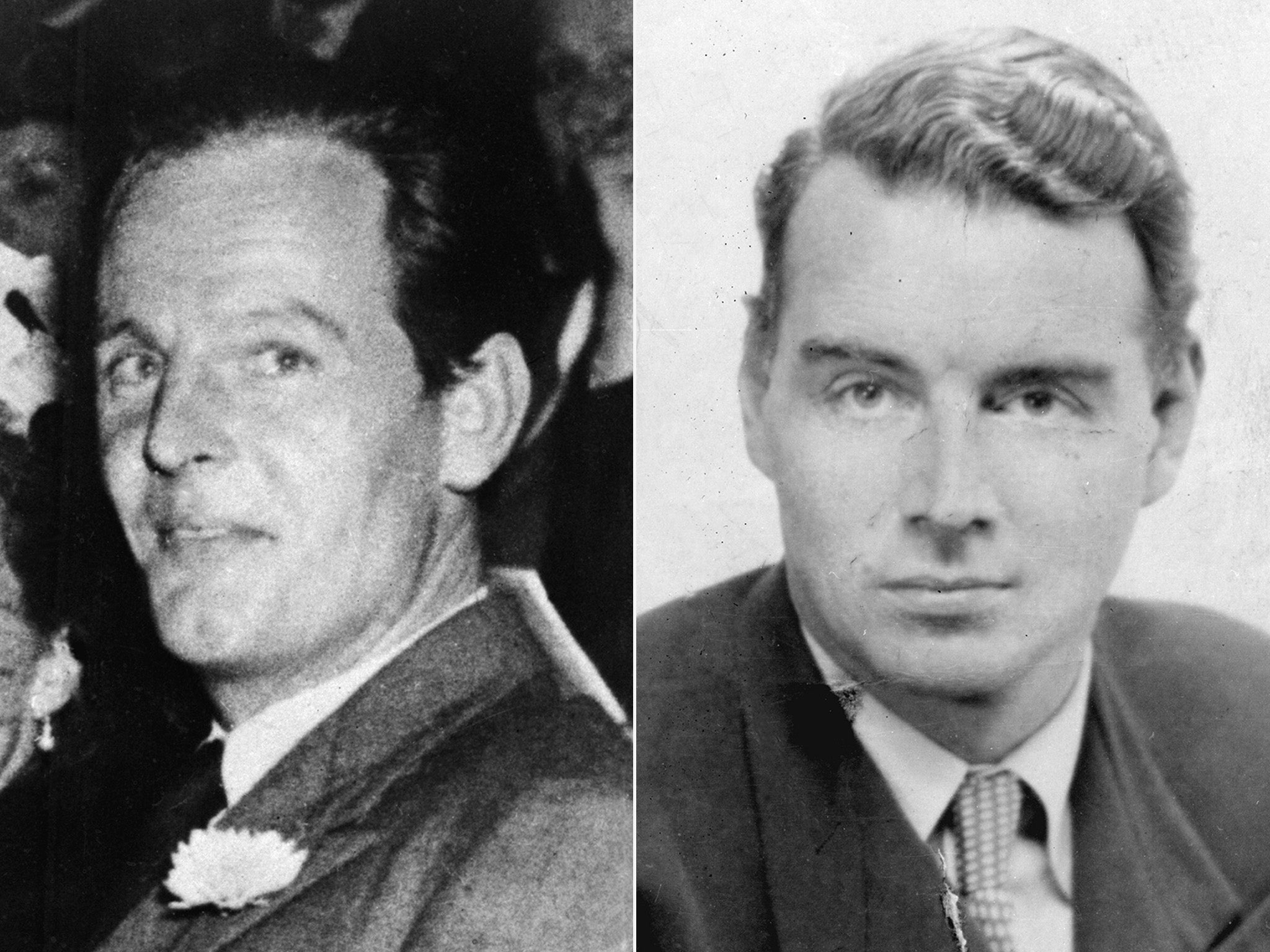

Philby was part of the “Ring of Five” – former Cambridge University students who passed information to the Soviets from the 1930s to the 1950s. The group included Anthony Blunt, Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, and John Cairncross.

Philby, often seen as the ringleader, also recruited Burgess and Maclean, later tipping them off in 1951 when Maclean was about to be unmasked. Their dramatic defections to the Soviet Union marked a turning point in Cold War espionage.

The Volkov Incident

One of Philby’s most treacherous acts, detailed in the files, was his exposure of Constantin Volkov, a KGB officer who tried to defect to Britain in 1945. Volkov approached the British consulate in Istanbul, offering a trove of intelligence in exchange for £50,000 and safe resettlement in the UK. The information included the identities of nine Soviet agents within the British establishment, seven in the Foreign Office and two in MI6. Among them was Philby himself.

Realising the danger, Philby sent an urgent warning to his KGB handler, took over the case personally, and ensured Volkov and his wife were kidnapped by KGB operatives. They were never seen again.

Volkov’s revelations could have been seismic. He promised to hand over not only the names of the agents but also a full list of KGB officers, safe houses, codes, and even keys to filing cabinets inside KGB headquarters. The files show Philby’s betrayal of Volkov as one of his greatest coups for the Soviet Union.

In his report from Istanbul, Philby misdirected attention, claiming, “The probable explanation is that Volkov betrayed himself. Either he, or his wife, or both, made some fatal mistake.” This calculated act ensured his cover remained intact and allowed him to continue operating undetected within MI6.

It was not until almost three decades later when he was working as a journalist in Beirut that his treachery was finally exposed in a confrontation with his longest-standing friend in MI6, Nicholas Elliott – when Philby also declared he would have done it all again.

Queen Elizabeth’s response to spy being her art adviser revealed

By 1972, wartime MI5 officer Blunt had become the late Queen Elizabeth’s adviser on art, with his involvement in the Cambridge ring only publicly revealed in 1979.

A note from March 1973 said the queen’s private secretary had spoken to the monarch about Blunt. “She took it all very calmly and without surprise,” it said.

The papers also disclosed Blunt’s vivid account of the group’s frantic final days – including that, amid fears of arrest and that their spy ring was about to be broken up, Blunt feared his KGB handler would turn violent when he refused to join his fellow spies Burgess and Maclean and flee to Russia.

Cairncross, the last of the spy ring to be publicly identified in the 1990s, admitted in a 1964 interview in the US that he too had been recruited by Russian intelligence.

“Cairncross has admitted spying from 1936 to 1951,” a telegram sent from Washington stated.

MI5 was baffled by ‘enigma’ Philby

Philby’s treachery first came under suspicion in 1951, following the defections of Burgess and Maclean. Summoned back to London, he was subjected to a bruising interrogation by Helenus “Buster” Milmo, a barrister working for MI5, who began by telling him not to smoke and accusing him of telling “a lot of half truths … downright falsehood”.

But while the session left many in MI5 – including Mr Milmo himself – convinced of Philby’s guilt, it failed to produce the conclusive evidence needed to take action against him.

So MI5 turned to Jim Skardon, a former Metropolitan Police Special Branch detective, who was renowned within MI5 after obtaining a confession from Klaus Fuchs, who betrayed the secret of the US-British Manhattan Project to build the world’s first atomic bomb to the Russians.

But Skardon, too, was unable to break Philby, concluding he was “more of an enigma than ever.”

Philby’s eventual confession to Elliott in 1963 remains a pivotal moment.

Elliott secretly recorded his conversation with his old friend in the Lebanese capital, with the transcripts vividly recounting the moment Philby owned up to a shocking betrayal on a personal as well as national level.

Transcripts reveal his acknowledgment of recruitment by the Soviet intelligence service in 1934 and his role in tipping off Maclean.

In reality, Philby continued spying for the Soviets throughout his time in Washington as MI6 station chief and during his subsequent years in Beirut.

Elliott confronted Philby in Beirut after MI5 secured proof from Flora Solomon that he had attempted to recruit her as a Soviet agent in 1934. Philby’s confession was a mixture of charm, deceit, and calculated misdirection. “As I recruited him [Maclean] in the first place the least thing I could do was get him off the hook,” he admitted.

Yet, the confession is riddled with lies, including the claim that he severed ties with the KGB in 1946.

Philby told of how he met with a man called “Otto” in 1934 at the behest of his wife Lizzy who was a Communist Party member.

“I explained my own position with great care, and he interrogated me at length. He maintained his offer, and I accepted,” Philby recounted of his recruitment in 1934 by a Soviet agent named “Otto” at the behest of his first wife, Lizzy.

“In short he proposed that I should work for an organisation which I was able to identify later as the OGPU (the Soviet secret police),” said Philby, who was given the codename “PEACH” by MI5.

In one chilling exchange, Elliott asked Philby about the Volkov case. “Presumably what you passed to them [the KGB] was mainly directed towards information of direct interest to them, like the Volkov business?” Elliott said. “Indeed,” Philby replied, before swiftly changing the subject.

Philby told Elliott he had no regrets, stating, “If I had my whole life to lead again, I would probably have behaved in the same way.”

Final betrayal and escape

In January 1963, after his meeting with Elliott, Philby vanished. He quietly boarded a Russian freighter in Beirut, leaving behind a note for his third wife, Eleanor, filled with vague reassurances. “My beloved, I have been called away at short notice. I am sorry I cannot be more explicit at the moment, but plans are somewhat vague. Don’t worry about anything. Tell everyone that I am doing a tour of the area. All love to your kiddies, and tons to yourself. Your, Kim.”

Philby fled to Moscow shortly after his confession and in 2010 was honoured with a plaque at the headquarters of the foreign intelligence service in Moscow – although he had died in exile years before in 1988, a lonely alcoholic.

Philby’s defection to Moscow marked the end of one of history’s most damaging espionage careers. From exile, he maintained contact with Elliott, expressing gratitude for what he perceived as a final act of friendship.

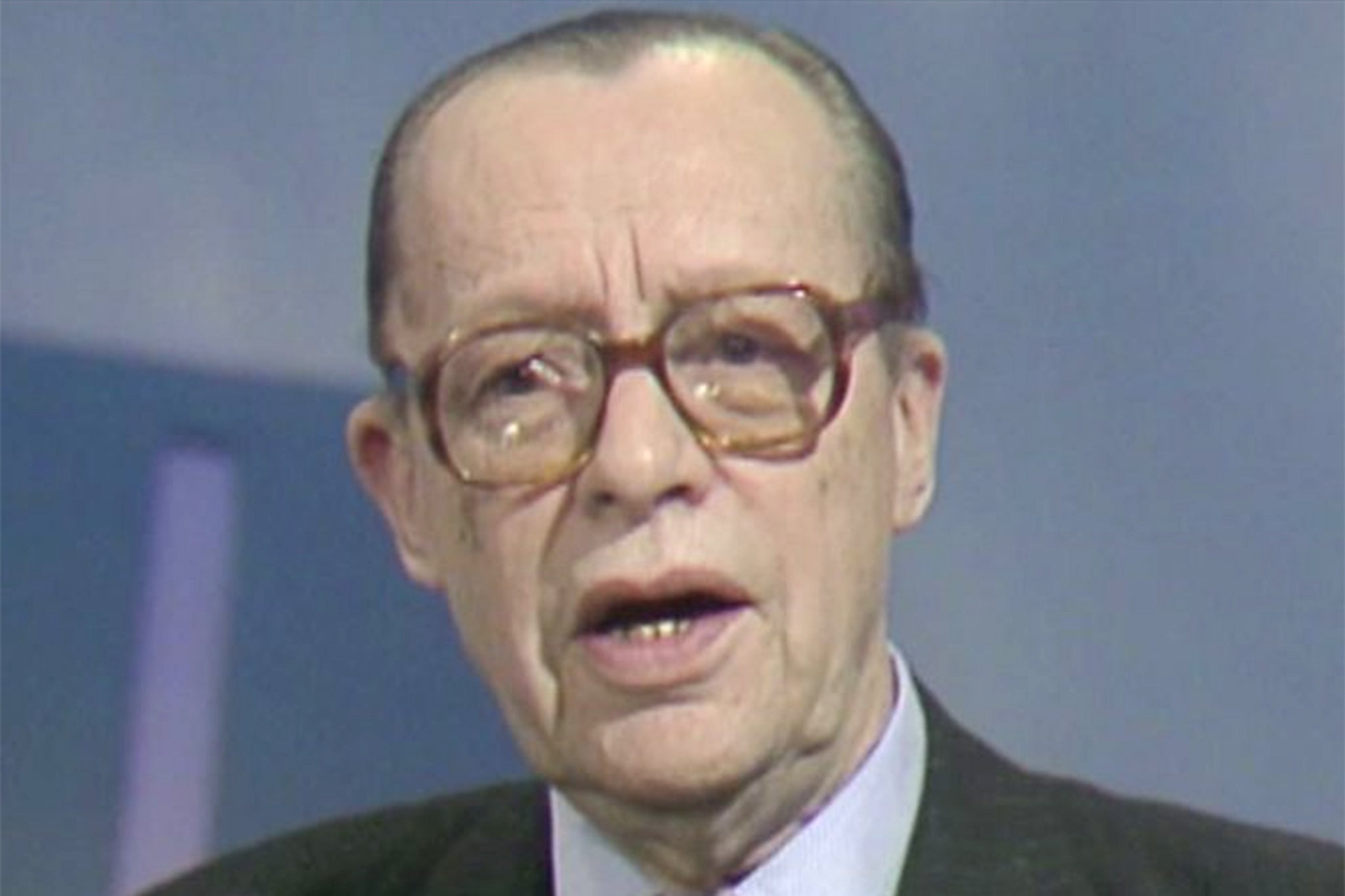

Whether Elliott deliberately allowed Philby to escape or was duped by his old friend remains a mystery, as Elliott took that secret to his grave in 1994.

This article was originally published by a www.independent.co.uk . Read the Original article here. .