Commercial platforms and social media companies are designed to maximise switching costs in order to retain users. Reflecting on the rise of Bluesky, Mark Carrigan warns the same market dynamics could ensnare academic Bluesky users.

After the US election there was a significant drop in users of Elon Musk’s now politicised X. There’s a risk of overstating the size of the exodus, given that at the time of writing Bluesky has 30 million users compared to what remains a larger userbase on X, even if these reported numbers are hard to trust. Yet, there are now thriving communities on Bluesky engaged in patterns of interaction eerily reminiscent of the early years of Twitter.

So why did it take academics so long to leave X? In asking the question, I realise I am in part interrogating my own motivations for remaining there until after the election. It feels awkward to explain that I was driven by the appearance of social capital to remain on a platform that I felt increasingly hostile to. I was acutely conscious that my university valued markers of public engagement, in this case a social media account with almost 10k followers, even if I rarely used it.

For other academics it was the reality of the social capital that left them bound into remaining on X, even if they felt increasingly uncomfortable with the culture of the platform. If you built a following on Twitter/X then leaving it unilaterally meant that you would lose your place within that network. This in turn could mean missing out on the appearance and reality of visibility that can feel significant in an anxious sector in the midst of a political and economic crisis.

Ultimately, I’m not sure it matters whether it’s the connections themselves, or the appearance of them, which leads academics to remain committed to a social media platform.

In my case a prominent personal academic blog, sites where I was a regular guest blogger and a Linkedin account, meant I was less concerned about losing my connections. In fact I was in the strange position of being engaged in slow project of shrinking my online network in support of my own wellbeing. Ultimately, I’m not sure it matters whether it’s the connections themselves, or the appearance of them, which leads academics to remain committed to a social media platform. The fact our working lives are now mediated in this way is however significant. Professional fortunes are now tied up in platforms that once seemed like liberating spaces, for example the impact agenda in the UK.

There are therefore significant switching costs for academics to move between platforms. Platform operate as walled gardens, they are closed ecosystems controlled by a particular firm, who impose costs on users who want to leave. Not only are the large platforms aware of this dynamic, they have actively built their strategy around it. For example in a recent book Cory Doctorow reflects on how the threat posed by Google’s social network Google+ was perceived by Facebook, as one executive claimed at the time:

“[P]eople who are big fans of G+ are

having a hard time convincing their friends to participate because 1/there

isn’t [sic] yet a meaningful differentiator from Facebook and 2/ switching

costs would be high due to friend density on Facebook.”

Google+ ceased operating in 2019, so

this executive’s confidence was well founded. However, this wasn’t simply a

neutral observation about how the platforms had developed, but rather a

reflection of a deliberate policy to maximise switching costs. If you make it

an ordeal for users to switch to another platform you fortify your own position

at the cost of user experience.

Bluesky is built on a protocol intended to mitigate this problem. The AT Protocol describes itself as “an open, decentralized network for building social applications”. The problem is that, as Cory Doctorow again points out, “A federatable service isn’t a federated one”. The intention to create a platform that users can leave at will, without losing their social connections, does not mean users can actually do this. It’s a technical possibility tied to an organisational promise, rather than a federated structure that enables people to move between services if they become frustrated by Bluesky.

The intention to create a platform that users can leave at will, without losing their social connections, does not mean users can actually do this.

This might not feel like a problem for

the platform now. But, what happens when investors start to pressure Bluesky to

increase engagement on the platform? What happens when a certain level of user

growth becomes a non-negotiable condition for funding? The reason other social

media platforms turned out the way they did is not due to the malign influence

of bad actors (though clearly they didn’t help), but rather due to the logic of

building a mass commercial social media platform. If you need it to operate at

scale, you design it in ways that shape user behaviour to this end.

The fact Bluesky has staff with patently good intention and the firm itself is a public benefit corporation doesn’t provide us with grounds to assume they will evade this trend. The problem is that, as Doctorow observes, “The more effort we put into making Bluesky and Threads good, the more we tempt their managers to break their promises and never open up a federation”. If you were a venture capitalist putting millions into Bluesky in the hope of an eventual profit, how would you feel about designing the service in a way that reduces exit costs to near zero? This would mean that “An owner who makes a bad call – like removing the block function say, or opting every user into AI training – will lose a lot of users”. The developing social media landscape being tied in the Generative AI bubble means this example in particular is one we need to take extremely seriously.

I could be wrong. Bluesky is certainly a much better place for academics to be than X. It would be a mistake to assume it will stay that way, given the forces likely to drive enshittification. It’s illuminating to compare this (partial) academic migration to Bluesky to the failed migration to Mastodon, analysed by Wang, Koneru and Rajtmajer. While there was an “initial surge in sign-ups” following Musk’s takeover, this “did not translate into sustained long-term user engagement” because “the level of established history, as well as the strong communities established on Twitter, with some over a decade, proved too significant to overcome”.

If it’s the community which holds academics in place, it raises the question of how we might better coordinate that community in future, recognising social media as the vital part of the research infrastructure that it has become. The tendency has been to see social media for academics as a trivial feature of professional life, whereas in reality it is now central to how academic networks form and reproduce.

Even though it’s become a routine feature of academic life it’s still treated as an individual matter, in terms of choices, training and regulation.

It can be difficult to recognise this significance because it’s far upstream from specific collaborations, but the things which academics do together (empirical research, scholarly communication, public engagement etc) now frequently feature social media in their origin stories, if not always necessarily in a central role. Even though it’s become a routine feature of academic life it’s still treated as an individual matter, in terms of choices, training and regulation. There’s little sense of strategic purpose concerning social media as a form of digital infrastructure upon which research collaboration depends, which leaves the sector precariously outsourcing it to unpredictable private corporations.

We’ve seen how badly this can work out in recent years with Twitter/X. Could we respond in a more organised and effective way to future waves of platform enshittification? I hope so, but it would require universities, as well as sector-wide organisations such as funding councils and learned societies, to recognise and take a stance in relation to these issues in a way they have thus far failed to do.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

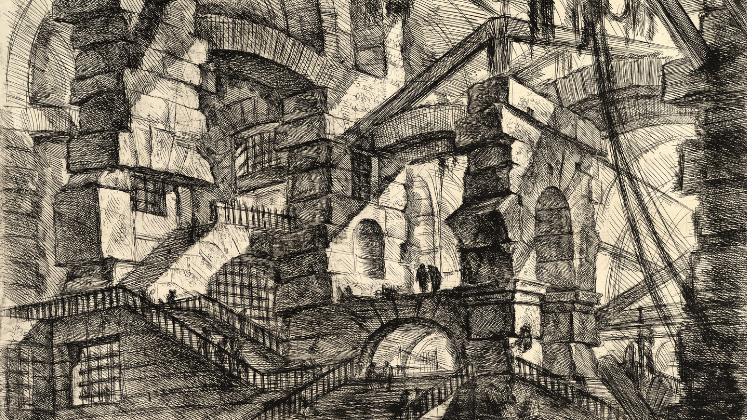

Image credit: Giovanni Battista Piranesi, The Gothic Arch, from “Carceri d’invenzione”, The MET (Public Domain).

This article was originally published by a blogs.lse.ac.uk . Read the Original article here. .